Authors

KRIS ROWLEY is an Advisor Director on the Data Foundation Board of Directors and serves as the Chief Data Officer of the non-profit Conference of State Bank Supervisors. He previously served as the first CDO at the U.S. General Services Administration

NICK HART, PH.D. is President of the Data Foundation. He previously served as the Policy and Research Director of the U.S. Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking and as an analyst in the White House Office of Management and Budget.

Contents

Introduction

In recent years, much has changed to establish a landscape and environment for successful data management in the United States federal government.

The advent of established Chief Data Officers (CDOs) across the federal Executive Branch reflects a renewed focus on data governance, and prioritization of data management and use in the public sector. The bipartisan Foundations for Evidence- Based Policymaking Act (Evidence Act) and OPEN Government Data Act, included a requirement for federal agencies to designate CDOs with a specific set of statutory obligations and functions relevant for the entire agency.[1] With many agencies now in compliance with a basic expectation from the law — identifying the individual to serve in the role of CDO — attention must be given to how a CDO can be positioned effectively within an organization to achieve success.

There are multiple, reasonable models that may be appropriate for agencies to employ in staffing, resourcing, and supporting new CDOs; there are also core criteria that agency heads must consider in the context of their agency’s respective mission and structures to ensure success. This white paper provides context for the new CDO roles in government, outlines core criteria for success of a CDO, and considers options for organizational placement and reporting.

Creating the Chief Data Officer Role

Building on an arc of advancements for open data in the federal government over the past decade, the Evidence Act and OPEN Government Data Act sought to address identified gaps and barriers in many agencies for actually using data. One major gap was the dearth of clear, sustained leadership to support data management activities. In 2017, the U.S. Commission on Evidence- Based Policymaking (Evidence Commission) recognized that most departments lacked senior leaders focused on data management.[2]

The Evidence Commission recommended the creation of a senior data management role in agencies, specifically focused on coordinating access to data and stewarding data assets for the agency.[3] It specifically envisioned the role as one that would coordinate within agencies and engage in outward-facing collaborations.

The new role proposed by the Evidence Commission, now known as a chief data officer, was added to the existing OPEN Government Data Act proposal and incorporated in the Evidence Act in 2017.[4] The provision requires that agency heads designate a non-political appointee with experience in “data management, governance, collection, analysis, protection, use, and dissemination, including with respect to any statistical and related techniques to protect and de-identify confidential data” as their CDO.[5] These extensive expectations were intended to signal the CDO position would cover a range of important and often deprioritized topics for promoting effective, responsible use of government data.

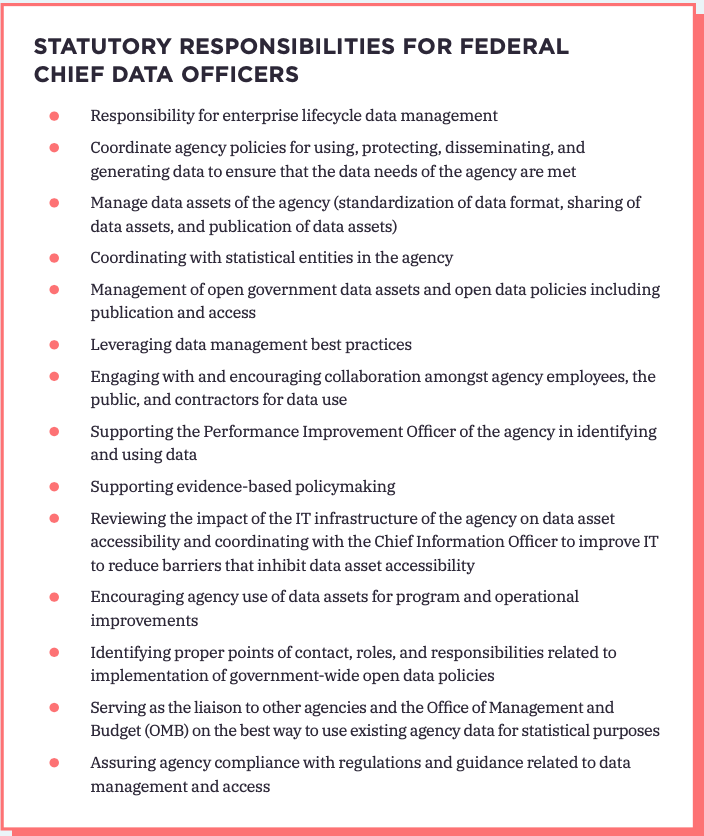

The law prescribes 14 core responsibilities for CDOs that cover issues ranging from enterprise data management to support for evidence-based policymaking.[6] These responsibilities designated for CDOs included issues that were not previously addressed in a systematic way by other existing agency leaders in most agencies prior to enactment of the Evidence Act. The Evidence Commission, for example, identified that Chief Information Officers in government already had expansive portfolios related to important systems procurement and cybersecurity issues, among others.[7] The Evidence Commission, therefore, did not recommend that the new responsibilities be assigned to Chief Information Officers. The Chief Information Officer community separately expressed concern about its ability to address data governance and open data expectations in government due to competing priorities.[8] For these reasons, Congress shifted the original OPEN Government Data Act designation of these responsibilities from the Chief Information Officers to support the new CDO function in agencies.[9] The Evidence Act pulled together multiple, previously decentralized and underprioritized data activities into a new central role. While many of these responsibilities were expected in the past, the Evidence Act provided the first government-wide formal expectation that agencies implement such responsibilities.[10]

Following enactment of the Evidence Act, OMB issued limited guidance on the role of the CDO, establishing deadlines for agencies to designate their officials and prescribing training opportunities coordinated by OMB. OMB’s guidance on the positions explicitly states an “expectation that these are full-time positions” and should be placed “in the best position” to fulfill statutory responsibilities."[11]

The federal government issued a comprehensive, government-wide data strategy that reinforced the role of the CDO in federal agencies.[12] The initial actions outlined under the data strategy called for CDOs to establish and chair agency data governance boards and also to convene the CDO Council created under the Evidence Act.[13] The strategy and action plan did not provide further guidance to agencies on how to structure the new CDO role within an agency, though a corresponding playbook on the data governance board provides some expectations about the need for collaboration and relationships to agency executive leadership.[14]

Key Considerations for CDO Structure within an Agency

While the Evidence Act, the Federal Data Strategy, and OMB’s implementation guidance to agencies do not prescribe how to structure the chief data office in an agency, there are core attributes that should be considered for effectively fulfilling the CDO role and expectations. A CDO should be able to:

Serve in an agency-wide leadership role with access to the agency head.

In order to serve as an effective organization-wide leader, CDOs need to be sufficiently senior within the agency with visibility into operational decisions and activities. The level of seniority is an institutional mechanism for providing access to collaborators, partners, and peers, while also minimizing levels of unnecessary bureaucratic oversight that could impede the CDO’s access to an agency head to assure data governance and management are adequately prioritized.

Establish an executive data governance body for the entire agency’s data needs.

Because the data governance body is charged with an agency-wide purview, the CDO must necessarily have knowledge about agency-wide data assets. As chair of the data governance body, the expectation is also that the CDO will partner with the Chief Information Officer and other senior officials who serve as members of the process. A CDO should be able to guide and lead the data governance process, including implementation strategies for effective standards, practices, and procedures throughout the agency.

Support agency learning agenda formation and use.

The Evidence Act charges agencies with developing strategic plans for evaluation and evidence needs, including by identifying relevant data gaps.[15] CDOs must collaborate with other senior leaders – including the Chief Performance Officer, Evaluation Officer, and Statistical Official when those positions exist in agencies – to develop a process for evaluating and addressing the key agency challenges as part of formulating agency learning agendas.[16] Supporting such collaboration may mean that the CDO needs to be organizationally positioned to be on par with these other officials, particularly in large agencies.

Drive culture change for applying technology to use data.

Leveraging the most appropriate emerging technologies can be valuable for efficiently addressing specific business and operational challenges in agencies. Shifting classic support structures and infrastructure to enable more effective use of new technologies and approaches requires organizational change management that drives a shift in culture to adopt, learn, and improve using such approaches. A CDO should be granted sufficient authority and encouraged by agency senior leaders to promote positive cultural change for data and technology use, consistent with strategic efforts to achieve the agency mission.

Articulate value for allocating resources to data governance.

The day-to-day activities of agency staff and program managers may not directly involve thinking about data governance or information quality. Yet the CDO is charged with prioritizing these topics and, in turn, explaining the value of improved data quality and the rationale for data standards across the agency’s program offices as a strategy for ensuring staff have the information in the form and of sufficient quality to make decisions or conduct analyses.

Identify and enable appropriate access to agency data assets.

Governing data must begin with the basic step of identifying what data are collected or managed by an agency. The CDO has an instrumental responsibility for developing and updating data inventories with appropriate descriptive information about the datasets. In addition, CDOs have a responsibility to coordinate access to such information, including when tiered access or other restrictions may be needed to protect against the risk of re-identification within an agency or from external users. Providing access to information within an agency is a collaborative process in partnership with agency technical staff, the Chief Information Security Officer and the Chief Information Officer to secure data properly.

Optimize enterprise technology and data platforms.

When it comes to centralizing or enhancing technological platforms used by an agency the CDO will rarely be able to act alone in such decisions, including facilitating data platforms and tools that are accessible to agency employees and partners. With systems procurement typically within the purview of the Chief Information Officer, CDOs should be able to collaborate to identify, procure, and sustain appropriate systems and analytical tools for the agency.

Manage and adopt new technology resources that support data-related initiatives.

CDOs can support and even oversee different applications and capabilities for data governance, management and use through the data governance mandate. Yet managing or overseeing technologies poses unique complexities in federal agencies when taken in conjunction with responsibilities and obligations of the Chief Information Officer under the Federal Information Technology Acquisition Reform Act (FITARA). CDOs can identify challenges, gaps, and synergies in partnership and coordination with the Chief Information Officer, including those with enterprise or agency-wide implications. This also includes introducing emerging technologies into data and technology platforms for use by analysts and researchers.

Each of these eight considerations for the role of a CDO in a federal agency may suggest a different option for structural or hierarchical placement and reporting.

Approaches for Structuring the Chief Data Office

Weighing which option is most appropriate for a given agency should involve reflection on personnel needs, leadership capabilities, resource availability, and expectations from within the agency and the stakeholder community. Choices about how to resource and staff a CDO will largely be determined by the choice of options below, though in no circumstance could a single individual likely fully achieve all of the expectations single-handedly in a large agency no matter who they report to.

Option 1: Report to the Chief Operating Officer

Federal agencies have a range of senior officials responsible for a broad array of functions. Today, many of those positions report directly to the Chief Operating Officer (COO) who is often a Deputy Secretary position and political appointee. Examples of existing chiefs that report to the COO include Chief Financial Officers, Chief Human Capital Officers, Chief Performance Officers, and Chief Information Officers. The reporting structure is perceived as an indicator of the priority the function takes within the institution. A CDO may be assigned as a direct report at this highest level of the agency, to the COO.

In practice, certain positions may report to other senior officials unless the reporting structure is identified in statute because it is more efficient or appropriate based on institutional systems and processes in place. Positions that are indirect reports, for example, may be viewed as less significant or important. The indirect reporting may also hamper the ability to identify and address major challenges facing a CDO, including access to senior-level discussions about priorities, major decisions, or involvement in strategic planning.

Practically, a COO can also only effectively manage a limited number of direct reports with an effective span of control. Too many chiefs may mean that positions or functions are lost among the many responsibilities, or deprioritized to the detriment of the function rather than delegated to another responsible party. The limited span of control has also led to the expansion of responsibilities for some other chiefs. For example, Chief Financial Officers often oversee Chief Performance Officers or are dual-hatted, meaning one person assumes both roles concurrently.

Notably, most COOs are political appointees, meaning they may be time-limited in positions with a focus on achieving short-term goals. In contrast, responsibilities of a CDO that may require changing cultures and long-term planning could be perceived to interfere with immediate needs and crisis management addressed by a COO. As a result, there is a risk that the expectations for the CDO may not align with the function and priorities of the leadership to whom they are reporting.

A CDO who is a direct report to the COO will need to identify funding, resources, staffing, and other operational and administrative duties that could distract from rapid progress or alignment of agency needs for data governance and management. However, a COO and supportive agency head can also ensure resources and personnel are aligned to fill this relatively new government function and expectation. Directly reporting to the COO will help alleviate some of the resource trade- offs that manifest when reporting happens through other individuals and units.

OPTION 2: Report to the Chief Information Officer

Chief Information Officers are largely charged with managing systems procurement, cybersecurity, and other core responsibilities for agency IT infrastructure and technology. Said another way, the Chief Information Officer typically focuses on the systems, whereas the CDO is charged with improving the quality of the information on systems, enabling access to that data, and promoting the use of data. While these activities are aligned with the Chief Information Officer capabilities, the CDO function is one that is drastically different.

Since the enactment of FITARA, most federal agencies have had Chief Information Officers which gradually had their roles and responsibilities expanded. Well- established Chief Information Officers have also tended to be well-resourced, funded through a variety of appropriations, set-asides, reimbursable authorities, and Working Capital Funds. The variation in funding capabilities is an advantage for potentially housing a CDO within the Chief Information Officer infrastructure, since the resources can provide needed support and personnel.

Prior to the statutory requirement for agencies to establish CDOs, many of the existing positions were situated within the Chief Information Officer umbrella in the limited number of agencies that voluntarily established the role. Agencies that acted in this manner may have also represented those agencies most likely where this model was to be successful in the sense that the Chief Information Officer recognized the need for the CDO function and that the Chief Information Officer themself could not fulfill the role.

Positioning the CDO within the Chief Information Officer unit may also be an opportunity to support maturation of the CDO function with the intent of eventually separating the units to create parallel structures that reinforce and support each other, along with other senior leaders in the agency. Of note, assignment of the CDO within the Chief Information Officer unit may support the alignment of processes for data governance that connect to other systems procurement and modernization efforts in the early stages of a CDO’s establishment.

A CDO in this structure, however, could have a limited ability to communicate directly with other senior officials in the agency and may have restricted reporting to the COO or agency head. Impeded communication could interfere with the ability to successfully communicate across an agency on data governance and management needs, as well as the implementation of a cohesive Data Governance Board.

Option 3: Report to Another Senior Official

Another option is for the CDO to report to an existing senior official that has a function related to data management and use. Such an official could include the Chief Financial Officer, a senior advisor for policy matters, or a data analytics or data management lead official. Such an arrangement could be relevant for the CDO in some agencies, particularly smaller agencies when dual-hatting officials may be common. However, in most agencies, other officials will likely be too distant from the core intended responsibilities of a CDO to be a good match for housing a chief data office.

Similar to integrating the CDO within the Chief Information Officer unit, other senior officials and units within an agency may offer an existing institutional infrastructure through which resources, staffing, and other processes could support rapid maturation of the CDO role.

Selecting an Appropriate CDO Structure

The process of selecting an appropriate reporting structure and approach for the chief data office in an agency will vary depending on agency characteristics, resources, expertise, and existing data maturity. Importantly, CDO positions established prior to 2019 when the Evidence Act was enacted may not be optimally positioned within agencies. Therefore, historic approaches to constituting a CDO function may not be ideal in the contemporaneous environment. Such arrangements may need to be reviewed closely by agency heads to ensure effective implementation of the new statutory requirements. Referring to those pre-existing models without properly assessing new laws and policies would be a missed opportunity. Instead, the placement of a CDO should be based on careful, considerate attention to the needs of an organization. The placement should not be based on convenience alone.

In any organizational placement scenario, agency heads should recognize the conditions under which a CDO will have a higher likelihood of success and where the CDO will have greater challenges. Ultimately, the CDO will be responsible for addressing a broad range of respons- ibilities and working across an agency’s organizational chart, but how an agency chooses to prioritize and structure the chief data office will affect the CDO’s and the agency’s success. Agency priorities will likewise contribute to informing what organizational structure will work best for a CDO.

In a 2020 survey of federal CDOs conducted by the Data Foundation, 86 percent of responding CDOs indicated they understood the expectations for their role, but only 54 percent had a clear concept of how they would be successful in fulfilling those responsibilities.[17] Identifying expectations and determining a path to success can be bolstered through an organizational arrangement suited to the agency and support from senior leadership, among other factors. In addition, CDOs identified that 9 of the top 10 focus areas for their efforts in the coming year were non-technical issues, like developing a data strategy, deploying data governance, and inventorying data assets.

The relationship with the Chief Information Officer is also a necessity, and success of CDO relies on a strong and consistent partnership with that official, in addition to other senior leaders. According to the Data Foundation’s 2020 CDO Survey, 96 percent of responding CDOs indicated that they collaborate with the Chief Information Officer on a daily or weekly basis. CDOs may also have dependencies or needs from the Chief Information Officer that differ from the dependencies or needs of other senior leaders in the agency. For example, the CDO has a clear dependence on technology and systems facilitated by the Chief Information Officer. But if the majority of major focus areas are non-technical, this dependency may be a minor issue for many current CDOs.

OMB’s past guidance for implementing the Evidence Act provides for considerable flexibility to agencies in determining an appropriate structure; the law itself provides no guidance on the matter. What is clear is that a one-size-fits-all approach does not exist.

The vast differences in size, structure, and mission of the federal government’s agencies makes consistent CDO organizational alignment impractical. The decision for how to structure a chief data office must be based on an approach that best fulfills the intent of the law, the expectations of the agency head, the maturity of the agency in enterprise technology investments, needs for performance management and evidence-based decision- making, and day-to-day data management activities. Additional factors may come into play as well, such as hesitancies for increasing overhead costs without additional appropriations, perceptions that new responsibilities within a particular agency may be well addressed by an existing position, and concerns about the span-of-control for the COO based on current obligations. These legitimate and important factors may be relevant in making a determination.

Next Steps for CDOs

As federal agencies work to implement the CDO function in compliance with the Evidence Act and to realize the benefits articulated in the Federal Data Strategy, careful consideration is needed upfront and with periodic reviews to ensure CDOs are positioned within the agency for success. Future OMB guidance could help agencies rapidly address some recognized challenges for structuring the CDO function, including by:

Providing more explicit guidance and direction to agencies on how to weigh appropriate considerations based on available resources;

Directing Chief Information Officers to work in partnership with the CDOs, including an expectation that in major agencies the roles are vital and cannot be fulfilled by the same person;

Emphasizing the need for ongoing coordination and collaboration between the CDO, Chief Information Officer, Chief Financial Officer, and other senior agency leaders; and

Encouraging agencies to periodically review the organizational placement and implementation strategy for the CDO to ensure success, while addressing competing organizational demands and strategic priorities.

The interagency CDO Council also has a vital role to play in advancing the institutionalization of the CDO function across government, including interagency collaborations on data governance, sharing, and use. Highlighting shared priorities, future opportunities, and the range of structural cautions among agency CDOs could be a role for the CDO Council to provide continued support for ensuring agency CDOs are organizationally situated to meet emerging government-wide needs. Regardless of agency size, reporting structure, or resourcing, the CDO Council can identify common focus areas and encourage collective strategies to address shared challenges by facilitating a strong community of practice. The established working groups of the CDO Council are well-positioned to address long-term issues like data standards, as well as short-term data integration and data sharing concerns among agencies.[18]

The options to structure of the chief data office have trade- offs within an agency under the multiple realistic scenarios, yet the role of the CDO in any case holds potential to substantially improve an agency’s management and use of data. Other organizational options may also be appropriate that merit further consideration by agency leadership, including considering different options between large and small agencies. But the decision about where to place or assign a CDO must be based on the desired outcome the agency head intends for the CDO to achieve – which hopefully stresses an arrangement where CDOs know what to do, how to do it, and are given the resources and support to succeed in accomplishing their task.

References

See Title II (OPEN Government Data Act) in P.L. 115-435. Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act.

U.S. Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking (CEP). The Promise of Evidence-Based Policymaking: Final Report of the Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking. Washington, D.C.: GPO, 2017.

See Rec. 3-3 in CEP, 2017.

Data Foundation. Future of OPEN Data: Maximizing the Impact of the OPEN Government Data Act. Washington, D.C.: Data Foundation, 2019. Available at: https://www.datafoundation.org/future-of-open-data-maximizing-the-impact-of-the-open-government-data-act.

Sec. 3520 in Title II of P.L. 115-435.

Ibid.

CEP, 2017.

U.S. House. Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. House Report on the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act (to accompany H.R. 4174). H. Rept. 115-411. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/115/crpt/hrpt411/CRPT-115hrpt411.pdf.

See original text for certain data governance responsibilities in the introduced version of the OPEN Government Data Act under the proposed Section 3565, which was later amended, in U.S. House. OPEN Government Data Act. Introduced as H.R. 1770 (not enacted version).

Hart, N. and Shea, R. “Focusing government’s C-suite on data quality makes good business sense.” The Hill. Washington, D.C., 2019. Available at: https://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/technology/445094-focusing-governments-c-suite-on-data-quality-makes-good.

See footnote 31 in Vought, R. “Phase 1 Implementation of the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018: Learning Agendas, Personnel, and Planning Guidance. Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies. M-19-23. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/M-19-23.pdf.

Vought, R. “Federal Data Strategy – A Framework for Consistency.” Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies. M-19-18. Washington, D.C.: White House Office of Management and Budget, 2019. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/M-19-18.pdf.

OMB. Federal Data Strategy 2020 Action Plan. Washington, D.C.: White House Office of Management and Budget, 2020. Available at: https://strategy.data.gov/assets/docs/2020-federal-data-strategy-action-plan.pdf.

OMB. Federal Data Strategy Data Governance Playbook. Washington, D.C. Available at: White House Office of Management and Budget, 2020. Available at: https://resources.data.gov/assets/documents/fds-data-governance-playbook.pdf.

Newcomer, K., Olejniczak, K, and Hart, N. Making Federal Agencies Evidence-Based: The Role of Learning Agendas. Washington, D.C.: IBM Center for the Business of Government, 2021. Available at: http://www.businessofgovernment.org/report/making-federal-agencies-evidence-based-key-role-learning-agendas.

Note the Evidence Act only requires this only from agencies specified by the CFO Act.

Data Foundation. Effective Data Governance: A Survey of Federal Chief Data Officers. Washington, D.C.: Data Foundation, 2020. Available at: https://www.datafoundation.org/effective-data-governance-a-survey-of-federal-chief-data-officers-2020.

Federal CDO Council. Report to Congress and the Office of Management and Budget. Washington, D.C., 2020. Available at: https://www.cdo.gov/assets/documents/CDO_Council_Report_to_Congress_OMB.pdf.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank several federal CDOs for their informal feedback on an earlier draft of this paper. The Data Foundation also thanks the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for their generous general operating support which enabled publication of this paper.