Authors

Steve Mumford, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Political Science and Public Administration, University of New Orleans

Nick Hart, Ph.D., President, Data Foundation and Chair, American Evaluation Association Evaluation Policy Task Force

Executive Summary

The Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act (Evidence Act) established new expectations for the evaluation field and practice across the largest federal agencies. While the goal of the law’s evaluation provisions is to enhance existing culture in federal agencies to produce and use evaluation, the requirements of the law focus on the people and processes to support capacity building. With guidance issued by the White House Office of Management and Budget in mid-2021, many federal agencies beyond those legally required to advance evaluation practices are also building capacity.

The survey of federal evaluation officials was designed by the Data Foundation in partnership with the American Evaluation Association. It provides exploratory and suggestive insights about the growth of evaluation practice in federal agencies, while also identifying early Evidence Act successes and challenges experienced by evaluation leaders. The survey specifically asked evaluation officials across federal agencies, bureaus, and operating divisions about their roles and experiences related to the Evidence Act and evaluation practice.

Key Findings:

The size of budgets and personnel to support evaluation vary greatly. Three-quarters of responding evaluation officials reported having five or fewer personnel or support contractors, and half of the respondents report evaluation budgets of one million dollars or less. A small share of offices include more than 25 people and more than $25 million. This captures the wide range of evaluation resources and staffing across government.

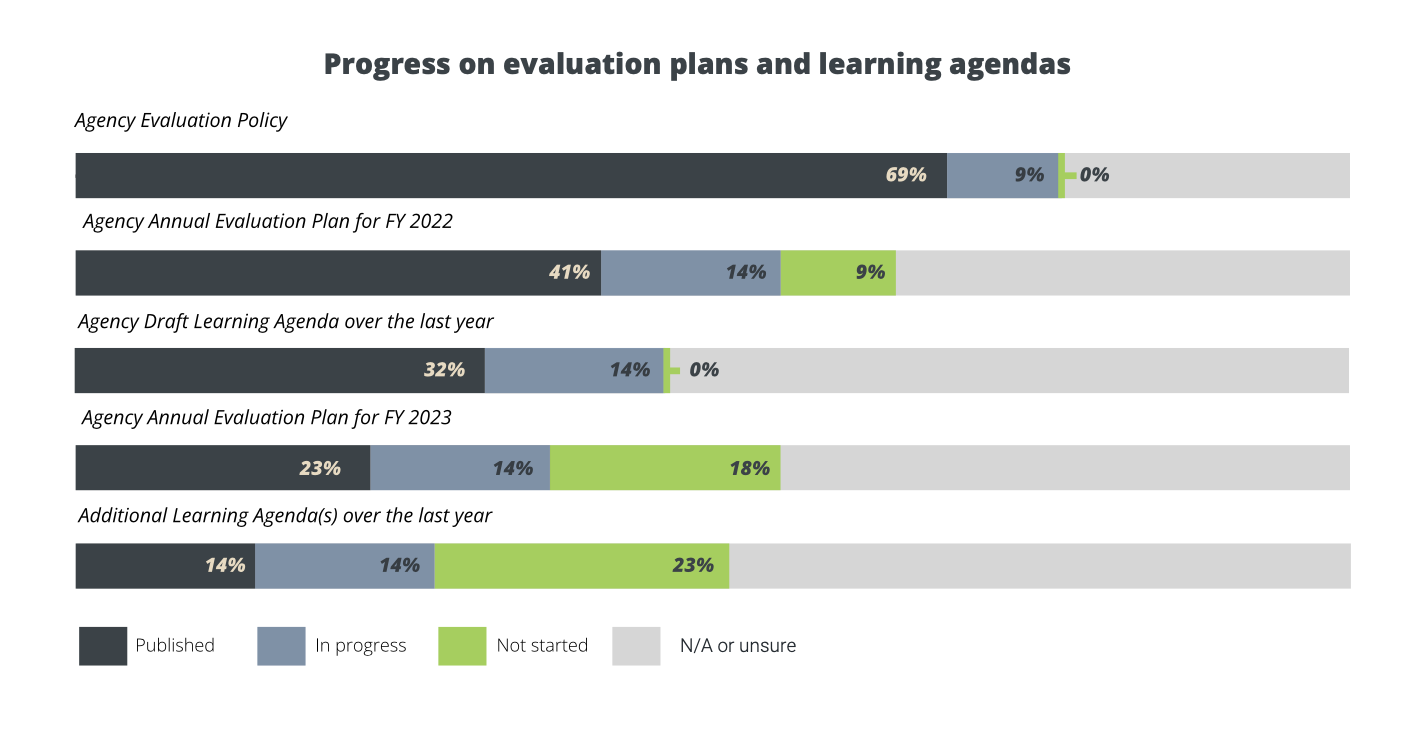

Implementation of Evidence Act evaluation provisions is progressing collaboratively. At the time of the survey in late 2021, two-thirds (68%) of respondents’ agencies had published an agency evaluation policy, and two-fifths (41%) published an agency annual evaluation plan for FY 2022. Respondents indicated high levels of collaboration with senior executives, statistical officials, and chief data officers in formulating agency learning agendas. They indicated collaboration with program managers in agencies typically weekly, but also reported relatively low engagement with external stakeholders.

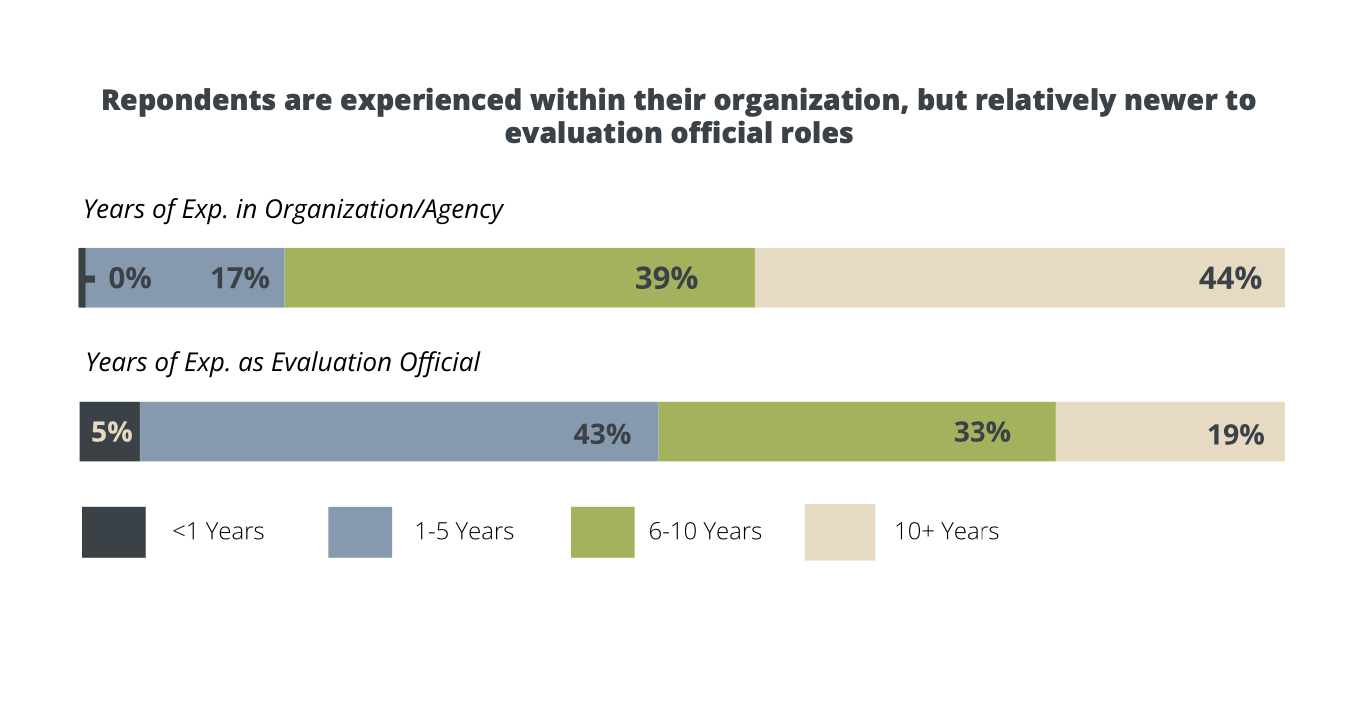

Evaluation officials are experienced and clear about their roles. Respondents represent a mix of designated Evaluation Officers and other evaluation officials, and 87 percent worked in the federal government for more than five years with 52 percent serving as an evaluation official for more than 5 years. Most (57%) perform duties beyond evaluation activities and also understand the duties of their role as an evaluation official (71%).

Evaluation officials are better positioned to support mission than prior to Evidence Act. A majority of survey respondents report their evaluation office has been “somewhat” (42%) or “very”(37%) successful at achieving their evaluation mission over the past year. Three- quarters (75%) perceive the evaluation community in their organization is better able to fulfill the evaluation capacity and process issues codified in the Evidence Act at the time of the survey than compared to 2018, before the Evidence Act was passed.

Use of evaluation results is lagging in many agencies. Evaluation officials responding to the survey indicated potential evaluation users in agencies have a limited knowledge of what evaluation is and how to use the results. The use of evaluation evidence was limited in different organizational tasks, including budget formulation and execution.

Evaluation officials need more resources and support for Evidence Act implementation. Among those who responded to the survey, evaluation officials recognized the benefits of the learning agendas and other planning processes yet expressed challenges created by limited resources and buy-in from senior leaders. In addition, respondents described an interest in additional training opportunities and strategies for engaging with stakeholders. Evaluation leaders’ success with implementing the goals of the Evidence Act and building sustainable evaluation functions across government will be substantially affected by capacity growth and targeted investments in coming years. Based on the survey results, key opportunities for supporting the evaluation function in government include:

Recommendation #1: OMB and agencies should request increased resources and funding flexibility in the President’s Budget request for specific evaluations and evaluation capacity, including personnel.

Recommendation #2: The Directors of OMB and the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) should accelerate efforts to issue guidance on the evaluation workforce and occupational series.

Recommendation #3: Agency heads should ensure Evaluation Officers designated by the Evidence Act are full-time positions.

Recommendation #4: Senior agency leaders should empower evaluation officials to conduct relevant educational and training initiatives about evaluation.

Recommendation #5: Senior agency leaders should establish clear expectations about when and how evaluation will be used in decision-making processes.

Recommendation #6: Congressional committees and staff should periodically contact Evaluation Officers and officials for updates on agency learning agendas and evaluation plans.

Recommendation #7: Congress should appropriate funds for evaluation capacity and evaluation products.

Recommendation #8: Evaluation officials should join together to proactively promote implementation of the Evidence Act, advocate for increased resources dedicated to evaluation, and support evaluation use among federal decision makers.

The growth in evaluation capacity, staff, and infrastructure is attributable to early champions, the Evidence Act, and the dedication of current evaluation officials to improving outcomes in their respective organizations. Federal evaluation officials indicate they are optimistic about the road ahead for the next year. With that optimism, the evaluation community, policymakers, and agency senior leaders must lend their support, encouragement, and enthusiasm for the evaluation endeavor to ensure that evaluative thinking is pervasive, evaluation practice is accepted, and evaluation use is expected throughout the federal government.

New Expectations for Expanding Government’s Evaluation Capacity

During the first meeting of the U.S. Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking in 2016, Co-Chair Ron Haskins declared that formalizing the role of evaluation in the federal government should be a top priority of the commission.[1] At the time, he was outspoken in advocating for the establishment of chief evaluation officers across government as a primary strategy for building evaluation capacity and resulting in more rigorous evaluations. The comments from Ron Haskins extended from work across the federal government to conduct and then use evaluation dating back to the 1970s. Yet, his plea reflected a growing sentiment about how to facilitate the growth of evaluation in government.

Over the preceding decade, the American Evaluation Association (AEA) emphasized the need for strategies to enhance evaluation policy and build capacity for the evaluation field across government agencies. In 2009, AEA published the first version of its Evaluation Roadmap for a More Effective Government, which outlines a framework for expanding capacity to conduct and use evaluation in government agencies.[2] Updated in 2019, the framework calls for the designation of senior officials to lead the evaluation function in government.[3] AEA’s Evaluation Roadmap also recognizes other aspects of capacity including written evaluation policies, quality standards, transparency of evaluation findings, and the preparation of annual evaluation plans.

For years, AEA advocated and encouraged growth in evaluation capacity within government. The publication of the Evidence Commission’s recommendations in 2017 cemented the call for evaluation leadership, process, and planning as part of the federal government.[4] Within a decade of AEA’s publication of the Evaluation Roadmap and three years after Ron Haskins’ plea, the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act (Evidence Act) required the 24 largest federal agencies to intentionally build evaluation capacity. [5] The Evidence Act required those agencies to designate evaluation officers, formulate annual evaluation plans, develop multi-year learning agendas (i.e., evidence-building plans), publish evaluation policies, and assess their existing capacity for evaluation.

With enactment of the Evidence Act, beginning in 2019, the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) directed agencies to designate their evaluation officials and begin planning for the key requirements of the new law.[6] OMB subsequently published guidance on agency evaluation standards and practices, which provided a framework that led agencies to publish their own policies.[7]

Shortly after his inauguration in 2021, President Joe Biden issued a memorandum to agency heads in the U.S. government recognizing the role of using evidence to inform policy.[8] AEA and the Data Foundation applauded the action.[9,10] That directive led OMB to issue new guidance to agencies in June 2021 about implementation of the evaluation provisions in the Evidence Act.[11] OMB’s updated guidance offered several important updates to how agencies would implement the Evidence Act:

First, the memo defined program evaluation as a core function of government. Just like human resources, information management, and financial management, OMB elevated the stature of evaluation activities to a function for agencies to implement as a cross-cutting support for programmatic activities.

Second, OMB noted that the legal requirement for the Evidence Act’s evaluation provisions applied only to the largest 24 agencies in government but at the same time encouraged all agencies to develop learning agendas and annual evaluation plans at the top level and in different units of the agencies.

Finally, the guidance from OMB in 2021 contextualized the important activities agencies were undertaking as part of the Evidence Act within the new Administration’s priorities and initiatives.

The guidance from OMB was widely praised by the evaluation community, including from both the Data Foundation and AEA.[12,13]

With the new expectations for the evaluation practice in government along with the anticipated growth in capacity, consistent mechanisms are needed to assess and inform ongoing implementation of these legal and policy expectations. This was the genesis of the Data Foundation and AEA survey of federal evaluation officials. The survey aims to provide reliable, public information about the growth of evaluation practice in agencies, while also identifying early Evidence Act successes and challenges experienced by evaluation leaders. Knowledge about the capacity and challenges for the federal government’s evaluation leaders can also inform future strategies for further advancing evaluation capacity, practice, and use, and establish a baseline for assessing growth in capacity through future annual surveys.

RESULTS OF THE 2021 SURVEY OF FEDERAL EVALUATION OFFICIALS

For the purposes of this survey, evaluation officials included individuals who were formally designated under the Evidence Act as well as other leaders of evaluation units within the 24 largest agencies covered by the Act.[14] In addition, because OMB’s guidance effectively encourages evaluation practice across the entire Federal Executive Branch, the contact list included identified evaluation leaders in dozens of other agencies not directly covered by the Evidence Act’s evaluation requirements. A total of 21 contacts completed the full survey (13% response rate), and 32 responded to at least part of the survey (20% response rate). Additional details about the survey methods are in the Appendix.

This survey specifically asked evaluation officials across federal agencies, bureaus, and operating divisions about their roles and experiences related to the Evidence Act and evaluation practice. This section summarizes the results and key findings.

The Survey Sample Represents Diverse Organizations

Survey respondents work within 12 of the 24 largest federal agencies directly covered by the Evidence Act’s evaluation provisions, as well as seven additional agencies. Three-quarters (77%) of respondents work within a designated evaluation unit or office in their organization, while 13 percent do not. Others noted the office is currently being created and staffed.

The size of budget and staff dedicated to evaluation activities within respondents’ organizations varies greatly, as does the degree to which organizations contract out evaluations. Among those evaluation officials who responded to the survey, their organizations’ current FY 2022 budgets directly supporting evaluation activities range from zero to $175 million. This wide range likely reflects the overall budget of the organization and the size of the agency. While half (50%) of respondents report an evaluation budget of one million dollars or less, a quarter (25%) report $50 million or more.

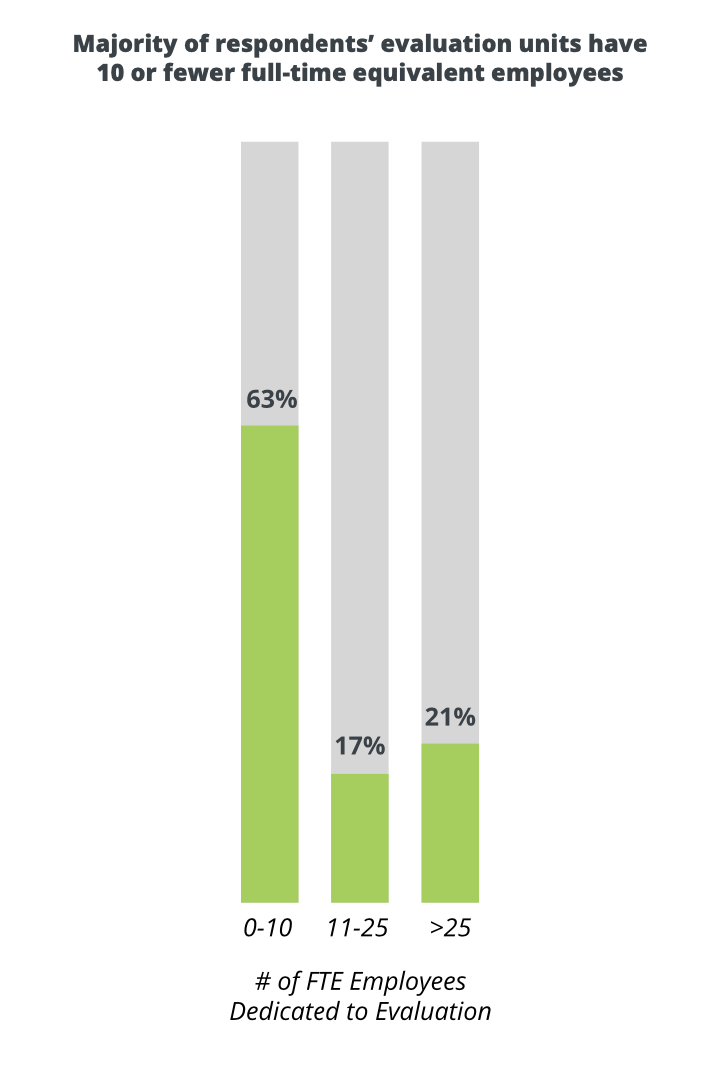

The number of full-time equivalent (FTE) federal employees in the respondents’ evaluation units dedicated to evaluation ranges from zero to 152 FTE. More than half (63%) of the units have ten or fewer FTE employees dedicated to evaluation, while one-fifth (21%) have more than 25 FTE. Likewise, respondents’ evaluation units rely on a varying number of contractors, fellows, and grantees dedicated to evaluation activities, ranging from zero to 35, with more than three-quarters (79%) reporting five or fewer contractors, fellows, or grantees.

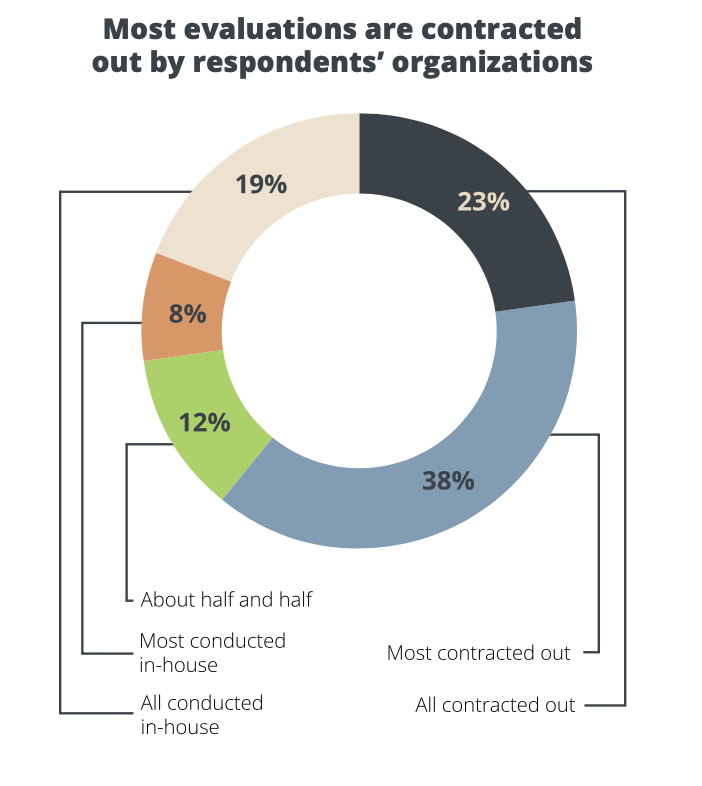

Put slightly differently, among all on-board employees dedicated to evaluation within an organization, the portion who are contracted out ranges from zero to 77 percent, although almost half (44%) outsourced one-third or more of their evaluation employees. Accordingly, how respondents’ organizations executed evaluation activities also spanned the full range, from contracting out all evaluations to conducting them all in-house. A large majority (73%) contracted out at least half of evaluations, and 62 percent contracted out most or all of them. Less than one- fifth (19%) conducted all evaluations in-house.

Respondents are Experienced and Clear on Their Multiple Roles

Almost half of the survey respondents (47%) are a designated Evaluation Officer (EO) by their Department Secretary or Administrator for implementing the Evidence Act. An additional one- fifth (22%) are not designated as an EO but serve as the senior evaluation official in their unit. About half (53%) act as evaluation official of any designation at the department or agency level, while the remainder act at the level of sub-agency, bureau, or operating division, such as Office of Inspector General (OIG) or a research and evaluation office within the agency or sub-agency.[15]

The large majority of respondents (82%) do not report directly to a member of the agency’s top leadership with wide purviews on resource allocations and decision-making, whether the Secretary or Administrator, Chief Financial Officer (CFO), Chief Data Officer (CDO), Chief Information Officer (CIO), or their deputy. Rather, survey respondents most often report to center or division directors or associate directors (e.g., of the evaluation unit), or the Inspector General or their deputy for those representing OIGs.

The large majority of respondents have more than five years of experience with the federal government (87%) and more than five years of experience with their current organization (83%). A majority (52%) have more than five years of experience in the role of evaluation official, and another 42 percent have been in their role for at least a full year. Most respondents (70%) stayed within their organization for as long as they worked for the federal government, but the large majority (90%) have not always been in their current role as an evaluation official. This pattern likely reflects that individuals designated as evaluation leaders were recognized for existing evaluation expertise in their organization or were designated as the most likely individual to develop evaluation activities in the organization.

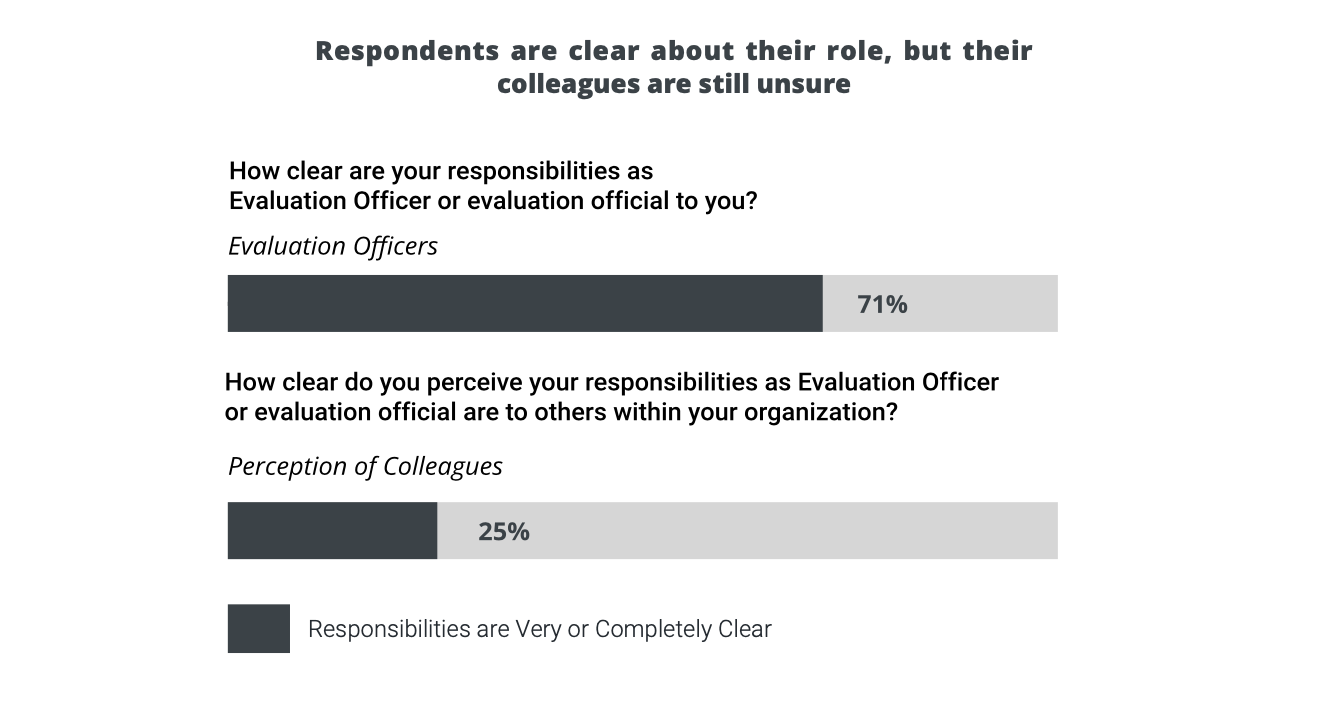

A majority (57%) of respondents report they perform additional duties outside their role as an evaluation official, most often involving performance and program management improvement. Additional roles and responsibilities mentioned by survey respondents include serving as chief or deputy Performance Improvement Officer (PIO), implementing agency-wide directives such as the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) and Executive Order 13985 on racial equity [16] , serving as Chief Data Officer (CDO), and overseeing the organization’s research and statistical efforts, such as risk and regulatory analyses, data management and analytics, audits, and technical assistance efforts. While this collectively suggests some related activities may be integrated with evaluation practice, it may also pose some risks in large organizations where evaluation officials are expected to cover an expansive range of responsibilities that may result in too little attention to evaluation-specific activities. One respondent indicated, despite their variety of responsibilities, respondents report that they are “very” clear on their responsibilities as an evaluation official. For Evidence Act-designated EOs, responsibilities delineated in both statute and OMB guidance provide additional clarifications about the role.[17] However, evaluation officials perceive their responsibilities are only “somewhat” clear to others within their organization. This may suggest future opportunities for education about evaluation and the roles and responsibilities of evaluation officials.

In addition to supervisory and budgetary responsibilities, I oversee a portfolio involving all agency activities for statistical surveys, grant monitoring and evaluation, performance reporting, research investigations, and other types of data collection/analysis activities.

Respondents are Collaboratively Implementing the Evidence Act

At the time of the survey in late 2021, two-thirds (68%) of respondents’ agencies had published an agency evaluation policy, and two-fifths (41%) published an agency annual evaluation plan for FY 2022. Even though the deadline was months away, about a quarter (23%) of respondents indicated their agency already published an evaluation plan for FY 2023, well before the beginning of that fiscal year. Based on OMB guidance at the time, the annual evaluation plans and multi-year learning agendas were not required to be published until early 2022. About one-third (32%) had published a draft learning agenda for their agency. While learning agendas are encouraged but not requested at the sub-agency level, 14 percent published learning agendas at this level.

When it comes to formulating priority questions for the draft agency learning agenda, respondents most frequently involve stakeholders from within their agency. The top three most involved stakeholders working with evaluation officials in the learning agenda process (between “to a great extent” and “somewhat”) are:

Senior executives and program administrators in the agency

Statistical officials in the department or agency

CDO in the department or agency

Senior political appointees are “somewhat” involved in formulating the learning agenda. The three least involved stakeholders in the survey (between “not at all” and “somewhat” involved) are:

Program beneficiaries or service recipients

Representatives of state and local governments

Representatives of tribal governments

In many respects, the relatively lower level of involvement among political appointees and external stakeholders may suggest areas for further education and coordination, as well as learning about effective mechanisms for engagement with non-federal stakeholders. For the 24 largest agencies, under the Evidence Act the learning agenda is designed to be part of the agency strategic planning process that involves senior leaders and executives.[18] The Evidence Act also requires consultation with stakeholders in the public, other agencies across levels of government, and the research community.[19] On the other hand, the higher level of engagement in the evidence community -- including managers and researchers — may suggest effective strategies for coordinating across those most likely to lead implementation of the learning agenda after its development and publication.

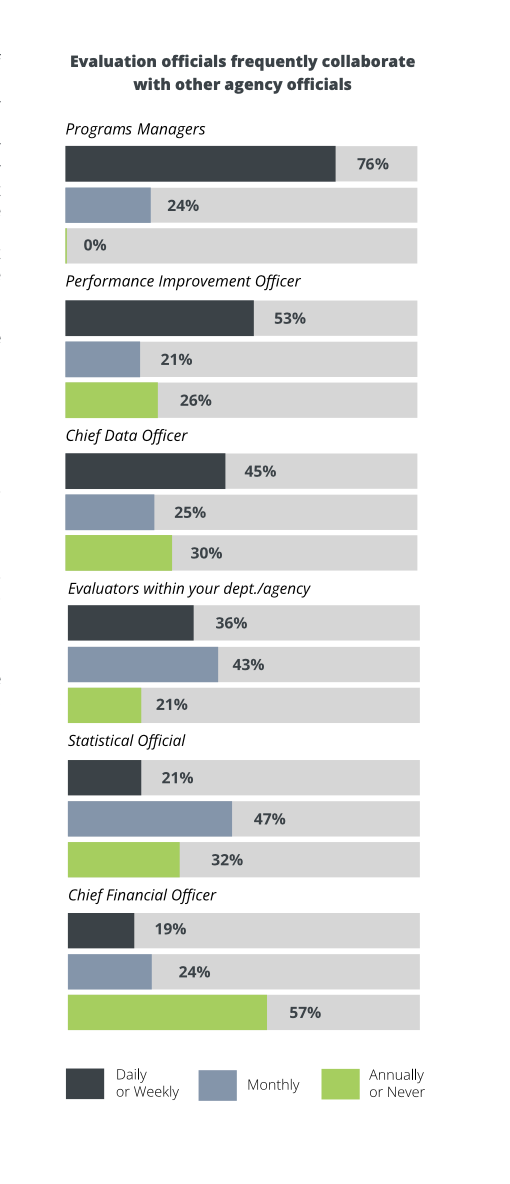

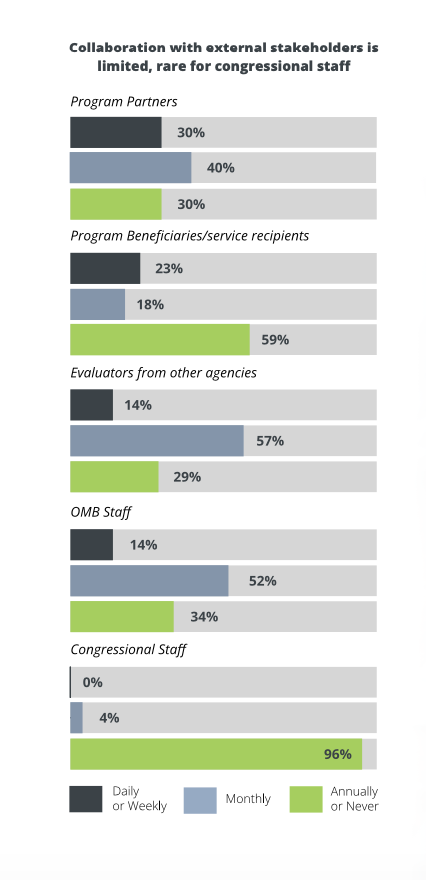

In general, in their roles as evaluation officials, respondents most frequently collaborate on evaluation activities with program managers, typically weekly. They collaborate with CDOs and statistical officials in their agency monthly, and with the CFO annually. Outside their agency, respondents collaborate monthly with program partners (e.g., states and grantees) and evaluators in other agencies, and slightly less often with OMB staff and program beneficiaries or service recipients. Most respondents collaborate annually, if at all, with congressional staff.

Evaluation Officials Support Agency Missions, Evidence Act Goals

The missions specific to respondents’ evaluation offices tend to support their agencies’ broader programmatic missions by providing evidence to guide decision-making and performance improvement. Responsibilities perceived by evaluation officials focus on setting agency-wide standards and policies in accordance with the Evidence Act, including coordinating the learning agenda and building an evaluation culture.

Sample evaluation missions:

“Support the development of evidence and to build capacity for program evaluation and research to help program managers deliver effective programs.”

“Coordinate the Department’s evaluation agenda and build the evidence culture in the Department.”

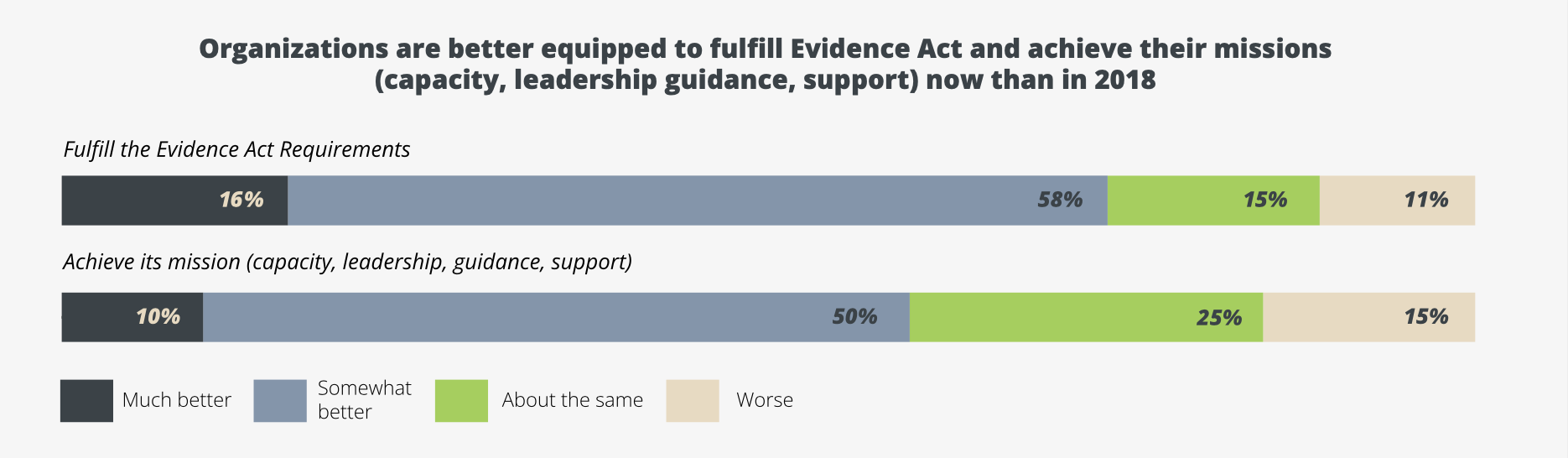

A large majority of survey respondents report their evaluation office has been “somewhat” (42%) or “very” (37%) successful at achieving their evaluation mission over the past year. Three-quarters (75%) perceive the evaluation community in their organization is better able to fulfill the evaluation capacity and process issues codified in the Evidence Act at the time of the survey than compared to 2018, before the Evidence Act was passed. Similarly, half (50%) perceive their ability to achieve their evaluation mission is now somewhat better, and 10 percent perceive it as much better. This collectively suggests that evaluation officers perceive that both the requirements of the Evidence Act and the implementation activities coordinated by OMB have been useful at fostering capacity for evaluative activities in federal agencies.

Respondents rated the importance of a series of different topics relevant for achieving their organization’s evaluation mission, including on evaluation capacity building. Large majorities found each topic area to be “extremely” or “very” important, but the three areas rated as most important for achieving the evaluation mission are:

Identifying areas of evaluation need for program managers (including for the annual evaluation plan)

Educating peers in the organization about evaluation

Educating leaders in the organization about evaluation

The emphasis on these topics among respondents also aligns with aspects of the Evidence Act and OMB guidance that focus on establishing processes and knowledge sharing about evaluation to build capacity in organizations. For agencies in the earliest stages of developing capacity, the planning activities are foundational for future efforts to implement increasingly rigorous evaluations.

In general, survey respondents described the learning agenda and implementation activities as meaningful in open-ended comments. Asked to share an example of how the learning agenda process or implementation benefitted their organization’s broader mission or goals, multiple respondents stated that the learning agendas helped with planning program activities, identifying gaps in existing data, and guiding resource allocation. Learning agendas also helped prompt strategic discussions about priorities at the agency level, orient new appointees and staff to the organization, reveal fundamental questions and relevant data assets or needs, focus research efforts, and voice to leadership what evidence is required to demonstrate meaningful performance improvement. One respondent expressed:

[The Learning Agenda process] prompted a constructive, strategic discussion of the fundamental questions underlying the business and what data assets are missing, but required, to formulate answers, [or] estimates.

Demonstrated in these survey responses, evaluation officials suggest that evaluation capacity building and planning processes can support larger organizational needs and inform program design. While it is too soon to determine whether the activities will result in more robust evaluation capabilities over the long-term, the short-term activities emphasize scoping, policies, procedures, and analytic approaches that align with the AEA Evaluation Roadmap’s operational principles.[20]

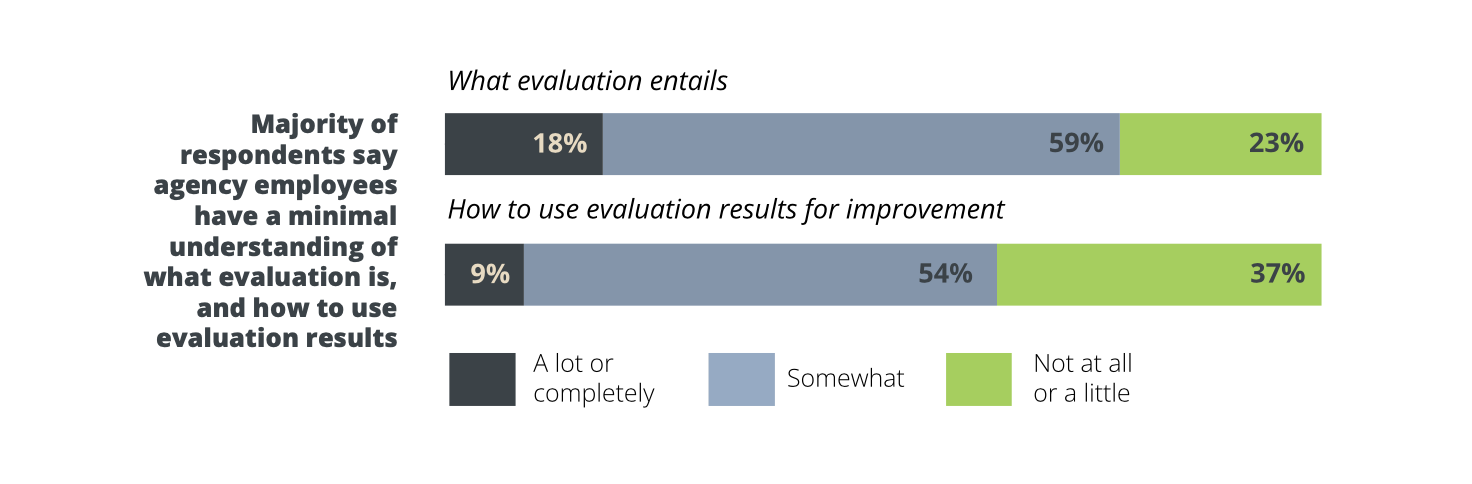

Use of Evaluation and Evidence Lags in Many Agencies

Most respondents believe employees in their organization “somewhat” understand what evaluation entails (59%) and how to use evaluation results for improving government programs and services (54%). The responses suggest room for improvement in bolstering organizational awareness of evaluative thinking and evaluation uses. For example, AEA’s Evaluation Roadmap includes a long list of possible uses of evaluation in practice to improve program effectiveness and efficiency, explain emerging problems, and identify innovative solutions, among other uses.[21] Evaluation officials who responded that their agencies are “not at all” or “a little” familiar with evaluation activities and uses may also benefit from near-term assistance from other agencies and the evaluation community to encourage knowledge sharing about the evaluation field and practice.

Respondents were asked how influential evaluation results are for decision makers in a series of routine organizational tasks , and the large majority also answered “somewhat” or less influential for each. The most influential area is strategic planning, which also includes the learning agenda process. Budget execution is the organizational task perceived by respondents to be the least influential area for the use of evaluation evidence, and budget formulation ranked only slightly higher. This perception may be related to how the federal appropriations process is executed, including on short timelines in recent years. For budget formulation, while OMB has required some activities to justify budget requests in developing annual President’s Budget submissions, the use of evaluation results would also be limited in this context if results are unavailable to support relevant budgetary decisions.

Our [Evaluation] Office is resourced well enough to conduct evaluations and gather sufficient data, however, we’re not properly resourced to effectively disseminate findings within the Agency that meaningfully impact strategic decision making.

Over half (56%) of respondents perceive that evaluation products have become “a little more influential” in the organization’s decision making since January 2021, while 39 percent think the level of influence remains “about the same.” Discussing the influence of evaluation products, two respondents said, both examples from respondents indicate the importance of evaluations being timed to decisions for relevant stakeholders. The first references the fast pace of some decisions, while the second describes the role of situational awareness for evaluations, so that decision makers are knowledgeable about how they can ask for evaluations in key decisions. Perceptions about receptiveness to using evaluation results also likely vary by individual political appointee, executive, and program manager over time. Monitoring for changes in this question may well be a leading indicator about evaluation use, or lack thereof, in federal agencies in the coming years.

Evaluation Activities in Agencies Face Limited Resources

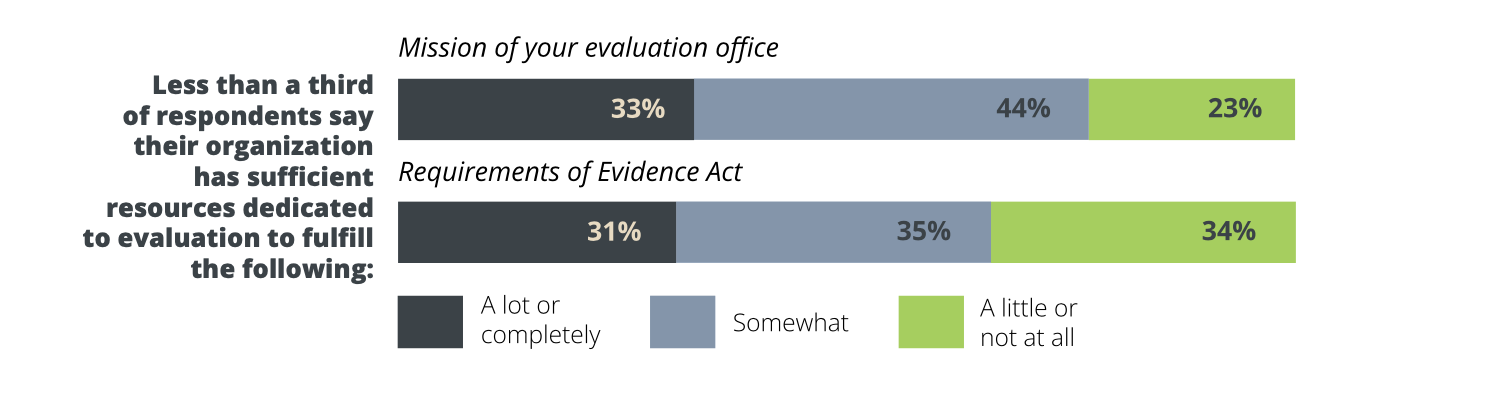

A large majority of survey respondents report that resources dedicated to evaluation to achieve the requirements of the Evidence Act (70%) and evaluation mission of their unit (67%) are “somewhat” or less sufficient. Respondents estimated that in order to effectively implement evaluation activities, they need their unit’s budget dedicated to evaluation activities to triple on average, and they need total staff FTEs dedicated to evaluation to increase by almost as much. Regarding the lack of funding to implement the requirements of the Evidence Act, one respondent observed that,

“ [M]ost programs do not have sufficient evaluation staff or funding to conduct needed/desired evaluation, as most funding is devoted to program implementation and performance monitoring. As the person responsible for Title 1 of the Evidence Act at my agency, I do not have the staff capacity to [do] anything but the basics regarding the Evidence Act.”

Large majorities of respondents identified the line-items in their evaluation budget for personnel and benefits, general or mission support contracts, and evaluation contracts as all “somewhat” or less sufficient. Resources for evaluation grants were perceived as least sufficient, with 86 percent responding grant funding is “a little” or “not at all” sufficient. This may reflect the relatively small number of evaluation units that provide grant funding for evaluation relative to resources allocated for grants through programmatic offices. Two respondents noted the frustration with the lack of a line-item in the following,

Respondents rated the resource sufficiency of a series of different operational areas for achieving their organization’s evaluation mission, and large majorities found each area to be “somewhat” or less sufficiently resourced. The three areas rated as least sufficiently resourced were:

Developing and training analysts and program evaluators

Conducting or executing program evaluations or analysis directly with federal staff

Leading formulation of the agency’s learning agenda and annual evaluation plan

Four-in-five respondents (80%) thought the learning agenda would be “somewhat useful” or “extremely useful” for helping to secure more resources for evaluation activities within their organization. Just 13 percent did not expect learning agendas to be useful in garnering more resources for evaluation.

Respondents Want More Support to Effectively Implement the Evidence Act, Including for Learning Agenda Formulation and Execution

Development of the learning agenda is one of the evaluation-related requirements of the Evidence Act intended to provide a pathway to additional capacity.[22] Yet many evaluation officials described challenges in their first effort to produce a learning agenda. The greatest challenges in formulating the draft learning agenda described in multiple responses to an open-ended survey question were the lack of organizational leadership’s commitment and incentives to comply with the Evidence Act and dedicated funding to carry out identified topics in the learning agenda, especially in smaller and more decentralized agencies not required to implement that requirement. Also mentioned were challenges with accommodating a wide variety of existing and new programs within the agenda and narrowing down questions and revamping plans in response to OMB guidance and feedback provided on draft plans. Respondents reported that,

To improve the process of formulating learning agendas, open-ended responses from multiple respondents suggest more ownership and buy-in on the part of Deputy Secretaries, senior executives, and program staff, and especially devotion of resources to the task, as part of a broader culture of continuous evaluation and learning. Respondents also suggested that OMB could help promote leaders’ support for evaluation by encouraging each agency to dedicate a minimum number of staff and funding for evaluation activities, a concept that has been discussed for years and was included among the detailed suggestions from the Evidence Commission.[23]

Respondents also named the top challenges “facing the broader federal evaluation community over the next year. The lack of evaluation staff capacity and expertise were mentioned most often, followed by a lack of funding for evaluation. Other frequent responses included the lack of organizational leaders’ and program managers’ use of evaluation and appreciation of its benefits, as well as simultaneously sharing data across “ agencies while protecting privacy.

Respondents identified the top areas where they need more support for evaluation in their organization, which generally align with the challenges noted above. More than half need more evaluation staff capacity and expertise. Slightly fewer need more support and advocacy for evaluation from leadership, or more attention to dissemination and use by program staff in activities like strategic planning and grant making. One-third need more funding for the evaluation function, including to conduct evaluations. Responses also acknowledged a need for more modern and secure information technology and data collection systems.

In terms of specific training or support needed for building evaluation capacity over the next year, more than half of open-ended responses proposed efforts to help leaders, program managers, and congressional staff understand the value and potential use of evidence and how to partner with evaluators. Evaluators, likewise, needed greater capacity to collaborate with stakeholders and report evaluation results in ways that encourage use. Respondents also perceived a need for additional technical training for evaluators in research designs, statistical techniques, applications of behavioral science, and use of information technology, including for securely linking datasets.

Finally, respondents shared their top opportunities for the federal evaluation community over the next year. Almost all respondents to the open- ended question saw potential for increasing interest in evaluation, especially as the Evidence Act and learning agendas gain buy-in and recognition among key stakeholders. Almost half saw opportunities for more collaboration and communication across federal agencies, particularly among evaluators sharing promising practices for evaluation methodologies and advocating for their profession within the government, including in partnership with statistical officials. One respondent noted in particular that,

In sum, while federal evaluation officials leading evaluation units identified many gaps and challenges in their current capabilities and capacity, they also highlight the promise of applying evaluation to inform agency decisions and improve program outcomes. The responses collectively strike an optimistic and realistic tone about the important role of evaluation and evaluators in government. The responses also demonstrate current evaluation officials’ dedication to growing the evaluation community in their agencies and continuing to strive toward effective implementation of the Evidence Act.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR EXPANDING FEDERAL EVALUATION CAPACITY

Evaluation leaders’ success with implementing the goals of the Evidence Act and building sustainable evaluation functions across government will be substantially affected by capacity growth and targeted investments in coming years. If evaluation officials are successful at achieving their evaluation mission then program administrators, decision makers, program beneficiaries, and taxpayers will be armed with more robust information about how the government is performing and what works in context. That information can ultimately result in improvements to the lives of the American people.

Recommendations for Executive Branch Leaders

The survey results indicate several clear areas where leaders and the policymaking community in the Executive Branch can engage to improve Evidence Act implementation, supporting enhanced capacity and activities for Evaluation Officers and evaluation officials more broadly:

Recommendation #1: OMB and agencies should request increased resources and funding flexibility in the President’s Budget request for specific evaluations and evaluation capacity, including personnel. The evaluation function must be adequately resourced within agencies to address the range of evaluative questions included in the agency learning agenda. This means that agencies need staff with the appropriate skills to manage contracts, conduct in-house evaluations, and collaborate with data officials across the government. Failure to adequately resource the function at the same time expectations of it are growing could undermine efforts to implement the Evidence Act beyond mere compliance.

With the designation of evaluation as a core function of government, OMB can ensure resources are requested that match the needs within the agencies. Agency evaluation officials can also work closely with financial managers and program administrators to facilitate allocations from existing program budgets to support data collection and evaluation.[24] In the end, agency evaluation officials should be willing to articulate resource needs so that adequate resources can be incorporated into budget formulation activities or new authorities for flexible funding mechanisms can be approved.

Recommendation #2: The Directors of OMB and the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) should accelerate efforts to issue guidance on the evaluation workforce and occupational series. The Evidence Act requires OMB and OPM to collaborate on a new occupational series or job categorization specific to evaluators. The evaluation function relies on qualified people to succeed. As the federal government works to improve staffing arrangements, evaluators with competencies that align with those published by AEA are critically needed.[25] Providing a job classification for evaluators will provide an additional vehicle to align evaluation expertise with critical needs in government.

Recommendation #3: Agency heads should ensure Evaluation Officers designated by the Evidence Act are full-time positions. For the largest 24 agencies in government, the role consisting of evaluation management, evaluation policy implementation, and coordination with relevant stakeholders is demanding. With the scope and scale of activities, large agencies are especially well-suited to ensure the role of Evaluation Officer is a full-time position for an employee of the agency. This also means that agency heads for large agencies should avoid “dual-hatting” Evaluation Officers with multiple designations, such as responsibilities for performance or budget. Agency heads should also review the level of reporting for Evidence Act-designated Evaluation Officers to ensure the position reports to the most appropriate senior-level official, such as a Deputy Secretary or Chief Operating Officer.

Recommendation #4: Senior agency leaders should empower evaluation officials to conduct relevant educational and training initiatives about evaluation. Evaluation officials reported challenges with receptivity to evaluation activities among others in their organization, which suggests an ongoing need to educate organizational leaders and program managers about the value of evaluation, including how results can be used to meaningfully improve program operations and outcomes. Capacity building efforts directed towards potential end-users of evaluation could create opportunities for evaluators to cross traditional agency siloes and share how evaluation created tangible benefits in their organization’s operational activities. Agencies could also align educational initiatives to data literacy programs and skilling efforts encouraged under the Federal Data Strategy and coordinated with the agency Chief Data Officer. This could, for example, include modules on interpreting evaluation results and using evaluation evidence in decision making as part of other regular data literacy program activities. In any case, part of this educational initiative should involve connecting the goals of evaluation activities to the core mission and programmatic activities across the agency, aligning missions and roles.

Recommendation #5: Senior agency leaders should establish clear expectations about when and how evaluation will be used in decision- making processes. Producing evaluations does not guarantee results will be used in decision-making. Devising clear procedural mechanisms for applying evidence and evaluation within established decision making processes could help generate and incentivize program offices to support evaluation activities. For example, decision memoranda to the Secretary or Deputy Secretary could include explicit sections about evaluation availability and results to inform major policy decisions. This approach would provide an incentive for managers approaching senior officials to be better prepared to support major decisions with evaluation findings.

Recommendations for Congress and Legislative Staff

Many of the challenges identified by evaluation officials in the survey could also be partially addressed with increased support and attention from Congress:

Recommendation #6: Congressional committees and staff should periodically contact Evaluation Officers and officials for updates on agency learning agendas and evaluation plans. The survey results indicate relatively low interaction between evaluation officials and congressional staff, yet the Legislative Branch is an important potential user of evaluation products. Whether inviting evaluation officials to brief Congress and staff on evaluation results, discuss the interim results of ongoing evaluations in the agency evaluation plan, or provide feedback on the agency learning agenda, collaboration with congressional stakeholders helps elevate the status of evaluation within the agency while also benefiting congressional decision making. Few evaluation officials participate in congressional briefings or receive invitations to proactively reach out to Congress on evaluation products. By facilitating a conversation about evaluation, the evaluation officials can also increasingly demonstrate the value evaluation provides to decision makers.

Recommendation #7: Congress should appropriate funds for evaluation capacity and evaluation products. With effective implementation of the Evidence Act and more evaluation products, Congress as an institution will be better positioned to effectively legislate. In 2021, the House Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress recognized the need for improved access to evidence in a public hearing and through its recommendation to address Congress’ needs for using evidence. [26] Providing funding for general capacity and specific evaluations in federal agencies through the annual appropriations process is a mechanism for building the infrastructure to sustain evaluation while also prioritizing issues for agencies and evaluation officials.

Recommendation for the Evaluation Community

Support for implementation of the Evidence Act is not solely the responsibility of program administrators or policymakers. The entire evaluation community, including those outside government, can contribute to bolstering the growing federal evaluation capacity:

Recommendation #8: Evaluation officials should join together to proactively promote implementation of the Evidence Act, advocate for increased resources dedicated to evaluation, and support evaluation use among federal decision makers. In 2022, as agencies begin publishing evaluation plans and learning agendas, the evaluation community can provide feedback and input about the planning documents while also offering expertise to help answer questions identified in the learning agendas. The evaluation community can also share its knowledge about resource needs with elected officials and other policymakers. As an example, AEA has in the past suggested to congressional appropriators the need for increased resources to support new Evaluation Officers.[27] Finally, the evaluation community can also share the results of federal evaluations, disseminate knowledge about the value of evaluation findings and uses, and continue to educate non-evaluators about the benefits evaluation offers to program administration.

CONCLUSION

However the survey results are read and used, it is clear that the evaluation function in government has made substantial progress in recent years. The growth of capacity, staff, and infrastructure is attributable to early champions, the Evidence Act, and the dedication of current evaluation officials to improving outcomes in their respective organizations.

As the evaluation function in the federal government continues to grow and mature, Evaluation Officers and officials will continue to face new challenges while realizing new successes. The successes will strengthen the culture that calls for evaluative thinking to support evidence-informed policymaking.[28] The challenges will provide new lessons to learn from and improve upon, demonstrating the very cycle of progress envisioned by the creators of the Evidence Act. One of these challenges will inevitably be shifting from capacity building activities to increasingly deliver ever-more-useful evaluation results that meet the demands from policymakers and program managers.

The era where evaluation was viewed as an extravagance available only to well-resourced agencies has closed. The requirements of the Evidence Act and the productive guidance from OMB in 2021 suggest evaluation is now a mainstay for federal programs. Every federal agency should now be expected to engage in evaluation. Even then, evaluators must still demonstrate value to gain buy- in and approval from agency leaders, stakeholders, and partners. Evaluation practices must still be considered at the outset and built into program designs. Resources are critically needed to scale capacity to meet the growing demand, including to deliver high-quality and useful evaluations that address priority questions.

Amidst the many obstacles, federal evaluation officials indicate they are optimistic about the road ahead for the next year. With that optimism, the evaluation community, policymakers, and agency senior leaders must lend their support, encouragement, and enthusiasm for the evaluation endeavor to ensure that evaluative thinking is pervasive, evaluation practice is accepted, and evaluation use is expected throughout the federal government.

Appendix: Survey Methodology

The 2021 Survey of Evaluation Officials was a collaborative partnership between the Data Foundation and the American Evaluation Association. The survey questionnaire was created by experts in evaluation policy, evaluation capacity building, and evaluation practice, including members of AEA and from among the federal evaluation community.

The research team compiled an inventory of evaluation officials within the scope of the survey, including Evidence Act-designated Evaluation Officers and officials leading evaluation units in federal Executive Branch agencies. The contact list was populated with officials identified from Evaluation.gov, federal agency websites, social media and professional communities, and Leadership Connect, a directory of government staff. The complete contact list included 158 valid contacts.

The Data Foundation emailed invitations to evaluation officials to participate in the survey by completing a web-based form from October 22 to November 15, 2021. Individuals in the sample frame were first contacted by the President of the Data Foundation, then invited to participate in the survey through a unique link emailed to them by a consultant working on behalf of the Data Foundation.

Non-respondents received up to four follow-up prompts to participate. Following the third attempt, non-respondents also received phone calls from Data Foundation staff to encourage response. While the survey was open, federal evaluation officials received another survey about evaluation competencies from the Office of Personnel Management, which may have introduced both survey fatigue and confusion about the differences in the survey approaches.

The response rate for complete responses in the survey was 13 percent, though partial responses elevated the response rate to 20 percent. Partial responses are included in the results where possible. Due to limitations in the size and potential representativeness of the survey sample, sub- group and multivariate analyses were not possible. Results should be considered exploratory and suggestive of future research.

Endnotes

U.S. Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking (CEP). First Meeting, July 22, 2016 [closed session].

American Evaluation Association (AEA). A Roadmap for a More Effective Government. [1st version] Washington, D.C.: AEA, 2009.

AEA. A Roadmap for a More Effective Government. [2nd version] Washington, D.C.: AEA, 2019. Available at: https://www.eval.org/Portals/0/Docs/AEA%20 Evaluation%20Roadmap%202019%20Update%20 FINAL.pdf

CEP. The Promise of Evidence-Based Policymaking: Final Report of the Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking. Washington, D.C.: GPO, 2017. Available at: https://www.datafoundation.org/s/Report- Commission-on-Evidence-Based-Policymaking.pdf

Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018, P.L. 115-435, Jan. 14, 2019.

Vought, R. Phase 1 Implementation of the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018: Learning Agendas, Personnel, and Planning Guidance. M-19-23. Washington, D.C.: White House OMB, 2019. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/ wp-content/uploads/2019/07/M-19-23.pdf.

Vought, R. Phase 4 Implementation of the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018: Program Evaluation Standards and Practices. M-20-12. Washington, D.C.: White House OMB, 2020. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/ uploads/2020/03/M-20-12.pdf.

Biden, J. Memorandum on Restoring Trust in Government Through Scientific Integrity and Evidence- Based Policymaking. Washington, D.C.: White House. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing- room/presidential-actions/2021/01/27/memorandum- on-restoring-trust-in-government-through-scientific- integrity-and-evidence-based-policymaking/.

AEA. Statement on President Biden’s Prioritization of Evidence-Based Policymaking and Evaluation. Washington, D.C.: AEA, March 22, 2021. Available at: https://www.eval.org/Portals/0/Final%20Scientific%20 Integrity%20Statement%203-22-2021.pdf.

Turbes, C. Prioritizing Scientific Integrity and Evidence-Based Policymaking. Washington, D.C.: Data Foundation. Available at: https://www.datafoundation. org/blog-list/prioritizing-scientific-integrity-and- evidence-based-policymaking/2021.

Young, S. Evidence-Based Policymaking: Learning Agendas and Annual Evaluation Plans. M-21-27. Washington, D.C.: White House OMB, 2021. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/ uploads/2021/06/M-21-27.pdf.

Data Foundation. Statement on OMB’s June 2021 Evidence Act Guidance to Federal Agencies. Washington, D.C.: Data Foundation, June 30, 2021. Available at: https://www.datafoundation.org/press- releases/ombs-june-2021-evidence-act-guidance-to- federal-agencies/2021.

AEA. Statement from the American Evaluation Association on the June 2021 White House OMB Guidance on Evaluation and Learning Agendas. Washington, D.C.: AEA. Available at: https:// www.eval.org/Portals/0/AEA%20Statement%20 on%20OMB%20Guidance%207_6_21_1. pdf?ver=hOXbF4fzWAhKp9ga0Z1MPQ%3d%3d.

Evidence Act officials are indicated on agency websites at www.[agency].gov/data and at www. evaluation.gov.

OMB guidance distinguishes evaluative activities for Inspectors General from other evaluation activities.

Biden, J. Executive Order on Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government. Federal Register. Washington, D.C.: GPO, 2021. Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/ documents/2021/01/25/2021-01753/advancing- racial-equity-and-support-for-underserved- communities-through-the-federal-government

See 5 U.S.C. 313(d) which lists four core functions of Evaluation Officers designated under the Evidence Act. See also Section IV of the Appendix to OMB M-19-23 which clarifies a more extensive set of functions and activities which the Evaluation Officers are expected to oversee.

See 5 U.S.C. 312(a).

See 5 U.S.C. 312(c).

AEA 2019, pp. 4-5.

AEA 2019.

Newcomer, K., K. Olejniczak, and N. Hart. Making Federal Agencies Evidence-Based: The Key Role of Learning Agendas. Washington, D.C.: IBM Center for the Business of Government, 2021. Available at: https://www.businessofgovernment.org/report/ making-federal-agencies-evidence-based-key-role- learning-agendas.

CEP 2017.

Fatherree, K. and N. Hart. Funding the Evidence Act: Options for Allocating Resources to Meet Emerging Data and Evidence Needs in the Federal Government. Washington, D.C.: Data Foundation, 2019. Available at: https://www.datafoundation.org/funding-the- evidence-act-paper-2019

Grayson, T. Letter to the U.S. Office of Personnel Management Director Re: Consultation on Program Evaluation Competencies Described in September 20, 2021 OPM Memo to CXO Councils. Washington, D.C.: AEA, October 12, 2021.

Hart, N. Testimony for the House Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress. October 27, 2021. Available at: https://www.datafoundation.org/blog-list/ written-statement-from-nick-hart-phd-president-of-the- data-foundation-for-the-house-select-committee-on- the-modernization-of-congress/2021.

Catsambas, T., L. Goodyear, A. White. Letter on Federal Appropriations for Evaluation. Washington, D.C.: AEA. Available at: https://www.eval.org/ Portals/0/Docs/Approps%20Request%208-1-2019.pdf.

Newcomer, K. and N. Hart. Evidence-Building and Evaluation in Government. Sage Publications, 2021.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the seven advisors to this project who provided invaluable advice and enthusiastic support for the design of the survey instrument and summary of results. The advisors included current government officials, former evaluation officers, and experts in evaluation capacity. The authors also thank Joe Ilardi for research assistance, Lori Gonzalez for editing, and Carrie Myers for graphics and design support. Lastly, the authors thank the evaluation officials who responded to our survey.

Disclaimer

This paper is a product of the Data Foundation, in partnership with the American Evaluation Association. The findings and conclusions expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the Data Foundation its funders and sponsors, or its board of directors.